The Quest for Better Teams

“Teamwork remains the one sustainable competitive advantage that has been largely untapped.” ~ Patrick Lencioni, Overcoming the Five Dysfunctions of a Team (Jossey-Bass, 2005)

Corporations increasingly organize workforces into teams, a practice that gained popularity in the ’90s. By 2000, roughly half of all U.S. organizations used the team approach; today, virtually all do.

A recent survey found that 91 percent of high-level managers believe teams are the key to success. But the evidence doesn’t always support this assertion. Many teamwork-related problems actually inhibit performance and go undetected.

While leadership and management styles have been evolving from autocratic to more participatory, the blurring of hierarchies and sharing of responsibilities have created other performance problems.

There are several barriers to achieving great work from teams:

- Some individuals are faster (or better) on key tasks.

- Developing and maintaining teams can prove costly and time-consuming.

- Some individuals do less work, relying on others to complete assigned tasks.

Team members aren’t always clear about roles and responsibilities, and members sometimes avoid debate and conflict in favor of consensus. Pressures to perform drive people toward safe solutions that are justifiable, rather than innovative.

Team members aren’t always clear about roles and responsibilities, and members sometimes avoid debate and conflict in favor of consensus. Pressures to perform drive people toward safe solutions that are justifiable, rather than innovative.

Despite these potential pitfalls, effective teams benefit from combined talent and experience, more diverse resources and greater operating flexibility. Research in the last decade demonstrates the superiority of group decision-making over even the brightest individual’s singular contributions.

The exception to this rule occurs when a group lacks harmony or the ability to cooperate. Decision-making quality and speed then suffer.

Beyond perfunctory team-building training sessions, what’s needed for teams to perform optimally? How can they evolve into resourceful, high-performing units?

Defining Your Team

Consultants Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith provide a solid definition of “team” in The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization (HarperBusiness, 2006):

“A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and an approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.”

Teams can be composed of 3 to 20+ members, but there’s often an ideal number: around 10 -12, depending on the nature of the project. They can, and should, be diverse to benefit from multiple perspectives, skills and knowledge.

Management professors Vanessa Urch Druskat, PhD, and Steven B. Wolff, PhD, identify three conditions essential to group effectiveness in “Building the Emotional Intelligence of Groups” (Harvard Business Review, March 2001):

- Trust among members

- A sense of group identity

- A sense of group efficacy

When working well, teams have definite advantages:

- Improved information-sharing

- Better decisions, products and services

- Higher employee motivation and engagement

What separates the good from the mediocre? What makes a team great?

Building Your Team

When a team first forms, members should identify their common goals and purpose. They can formalize their mission in a meeting that identifies these basic organizational issues:

- Core purpose

- Core values

- Business definition

- Strategy

- Goals

- Roles and responsibilities

Team members must have a shared understanding of the business before they define their purpose. Without this foundation, group cohesiveness is more difficult to achieve.

Next, team members should list what they intend to achieve as a group. This goal should be qualitative rather than quantitative.

Thematic Goals

Lencioni advises team members to identify a “thematic goal” that answers the following question:

“What is the single most important goal that we must achieve during this period if we are to consider ourselves successful?”

Examples of thematic goals include:

- Improve customer satisfaction.

- Control expenses.

- Increase market awareness.

- Launch a new product.

- Strengthen the team.

- Rebuild the infrastructure.

- Grow market share.

Choosing a thematic goal doesn’t mean that other goals are ignored. A thematic goal ensures that every team member emphasizes a core priority, thereby creating team alignment, minimizing paralysis and frustration, and avoiding a collective silo mentality (i.e., hoarding information).

Putting the “TEAM” in Teams

Effective teams excel in the following functional areas:

T = Trust (shared vulnerability and empathy)

T = Trust (shared vulnerability and empathy)

E = Engagement (shared goals, commitment and debate)

A = Accountability (personal and peer-to-peer conversations)

M = Metrics (focus on the right measurements for the right results)

Trust

Nothing is more important to team success than a solid foundation of trust. Unfortunately, this can be hard to achieve. People are dedicated to self-preservation, often at others’ expense.

“When it comes to teams, trust is all about vulnerability,” Lencioni notes. “Team members who trust one another learn to be comfortable being open, even exposed, to one another around their failures, weaknesses, even fears.”

Trusting relationships form the foundation for forgiveness and acceptance. Authenticity depends on members’ willingness to admit weaknesses and mistakes. Trust cannot exist if team members are afraid to say:

- “I could be wrong.”

- “I messed up.”

- “I’m not sure.”

- “I need some help here.”

- “I’m sorry.”

Team-building sessions are the glue that holds the group together when the going gets rough. Trust is established when one team member shows a willingness to be vulnerable and takes personal accountability.

Team-building sessions are the glue that holds the group together when the going gets rough. Trust is established when one team member shows a willingness to be vulnerable and takes personal accountability.

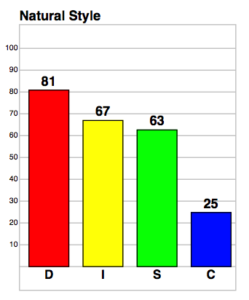

Managers can also build trust by sharing personal assessments such as the DISC behavioral assessment which we provide to our clients. When team members learn how different behavioral styles deal with tasks and relationships, they can be more understanding and accepting of varying approaches to day-to-day activities.

Engagement

Think of engagement along a continuum. On one end there’s complete apathy, disengagement and perhaps even sabotage (the ultimate form of negativity). On the other end there’s total engagement (unbridled enthusiasm and passion).

Engagement requires team members to be open to debate and willing to discuss the issues and tasks that matter most. Members who succumb to apathy and disengagement often don’t feel safe enough to speak up. Lencioni cites this desire to avoid conflict as one of the most pervasive team dysfunctions. Others include:

- Lack of trust

- Lack of commitment

- Avoidance of accountability

- Inattention to results

When trust has been established, team members can safely argue about issues and decisions that are critical to success. They’re comfortable disagreeing with each other, challenging perspectives and questioning premises in an effort to find the best answers. They’re willing to consider all opinions and possibilities to arrive at sound decisions.

Active debate means team members can achieve a consensus (not necessarily unanimous) and commit to action steps.

“If team members are never pushing one another outside of their emotional comfort zones, then it is extremely likely that they’re not making the best decisions for the organization,” Lencioni notes.

Accountability

Team members who commit to decisions and performance standards aren’t afraid to hold one another accountable. In fact, they invite suggestions that help each member stay on task. Peer-to-peer accountability conversations are essential to maintaining focus and monitoring progress.

Team members should agree on set phrases to remind each other of what matters most. They can help each other out by noticing distractions and steering efforts toward accomplishing thematic goals. Groups should be encouraged to ask key questions on a regular basis:

- Will this issue or task help us reach our goals?

- I notice _______ hasn’t been finished. What do you need to get it done?

- What resources are missing here?

Effective team members are quick to spot problems and are willing to speak up without assigning blame. They cooperatively seek solutions.

Metrics

Highly functional teams focus on group efforts and avoid seeking personal gains, fulfilling career aspirations and/or boosting individual egos. They use metrics to assess their achievements – be it a simple whiteboard or a sophisticated online tracking tool.

Highly functional teams focus on group efforts and avoid seeking personal gains, fulfilling career aspirations and/or boosting individual egos. They use metrics to assess their achievements – be it a simple whiteboard or a sophisticated online tracking tool.

Success depends on monitoring progress and posting results for all members to see. Results should be updated regularly so any necessary adjustments can be made.

Teams should learn to provide positive feedback and recognition for progress – key motivators that renew energy and drive.

Identify Gaps

Assess your team by asking each member to answer two questions confidentially:

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how well are we working together as a team?

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how well do we need to be working together as a team?

Calculate for each area of functioning in the TEAM acronym and discuss the results. According to research involving several hundred teams in multinational corporations, the average team member believes his/her team operates at a 5.8 level of effectiveness, but recognizes the need to be at an 8.7.

Discuss and explore performance gaps. Ask team members for ways to improve trust, engagement, accountability and metrics. After making a list, choose one behavioral change that everyone can agree to prioritize.

Set up a team score card to track and recognize progress for each element of effectiveness in the TEAM. Make team-building a regular part of your meetings.